Higher home care wages reduce economic hardship and improve recruitment and retention in one of the country’s fastest-growing jobs

Washington State hazard pay program shows impact of higher wages on caregivers and long-term care

By: SEIU 775 and the Center for American Progress

Executive Summary

Home care workers provide support to people with disabilities and older adults so that they may receive care and remain in their own homes. Widely preferred by care recipients and the aging adult population, home care is one of the fastest-growing jobs in the country. Yet home care workers – who are disproportionately women, and Black, Indigenous, and people of color – are under-paid and undervalued, contributing to chronic staffing shortages and high turnover in the field.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, some states used the emergency influx of federal Medicaid dollars to implement hazard pay, a significant but temporary increase in home care workers’ wages. This case study is based on in-depth interviews and a statewide survey sent to 42,000 caregivers and completed by 5,307 caregivers who received hazard pay in Washington State. It provides evidence that even a $2.50 increase in home care wages yields significant measurable improvements in caregivers’ housing and food security, access to healthcare, mental health, savings, and well-being – as well as their ability and willingness to take and stay in these critical jobs.

Caregiver Lauren Evans is no longer experiencing homelessness. For the first time in years, she and her three kids have an apartment of their own. Tyrone Leach is relieved of chronic stress, saying, “I no longer have to worry about juggling bills. I know I’ll have enough to pay everything.” Sunshine Lopez always lived paycheck-to-paycheck, but now has a savings account and paid off $5,000 in debt. For Brenda Morgan, hazard pay is the joy of buying a washer and dryer and taking her family out for ice cream on Sundays. Sarreh Jarju still works 80 hours a week, but she no longer has to go to the food bank or pray that her kids will have enough to eat. She explains, “My friends see that I am happier now [and] ask what my secret is. I tell them [it’s] no secret, it’s because [my] Union fought to get hazard pay.”

“For years, my kids and I lived with my mom because we couldn’t afford to live anywhere else. But in January of 2021, with the money from hazard pay, we were finally able to get our own place. It’s the cheapest I could find: an apartment complex for low-income tenants in a unit with just two bedrooms for the four of us. I make just enough to cover it. I dream of having enough money to give my kids their own rooms, but at least we have a home right now. If our wages drop back down, I’m scared we’ll have to move out. I’ve lived on my own in a car before, [and] I will never forget what it feels like not to have a home to go home to. That freaks me out, especially since I have kids.”

— Lauren Evans (Vancouver, WA)

On every indicator of economic security measured in the survey, hazard pay produced significant improvements in caregivers’ lives (see chart on Page 2 summarizing key indicators). Black, Indigenous, and caregivers of color, as well as caregivers who speak a language other than English and caregivers raising children often experienced the most economic hardship before hazard pay and saw the biggest net improvement from higher wages.

The impact of higher wages on caregivers’ economic security and well-being also translates to their ability and desire to stay in the job. Caregivers described their love for their clients and their work, but many also said they have considered quitting due to low wages. When surveyed, many caregivers reported that higher wages recruited them to the field or encouraged them to stay:

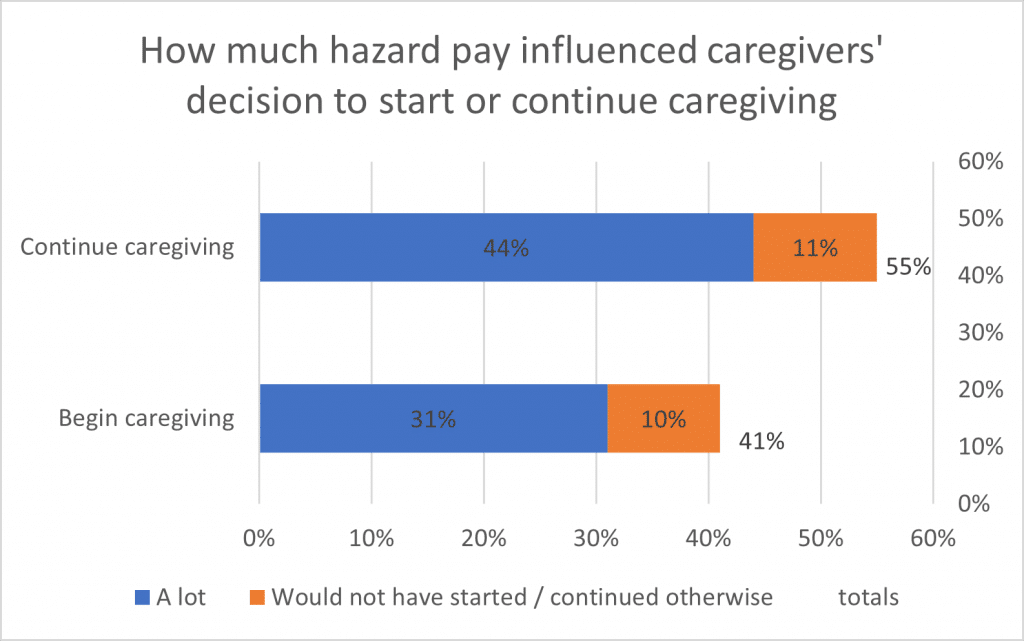

- 41% of people who began caregiving within the last year said they would not have started without the higher wages or that the higher wages had a big influence on their decision to start.

- 55% of caregivers who have been in the field longer than one year said they would not have continued without the higher wages or that the higher wages had a big influence on their decision to continue.

Higher wages will help to ensure that there are enough caregivers to meet the growing demand, and that there are caregivers with enough long-term experience in the field to provide quality care.

As Congress deliberates over investments in long-term economic growth, expanding access to quality, affordable home care will help hundreds of thousands of older adults and people with disabilities obtain the support they need, while also creating jobs, raising wages, and reducing economic insecurity and racial inequity. Following the guidance in President Biden’s American Jobs Plan, Congress should invest $400 billion in expanding Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) under Medicaid to both expand access to services and improve wages and benefits for home care workers. Such an investment would attract and retain workers, afford people with disabilities and older adults the opportunity to receive care in their homes, and ensure that caregivers and their families have the resources they need to live with dignity.

| Economic Security Indicator | Before Hazard Pay | After Hazard Pay | Net Improvement (percentage points) | Disproportional Impact & Net Improvement |

| Overall economic well- being. — “Just getting by” or “finding it difficult to get by” | 66% | 16% | 50 | Indigenous caregivers: 72% to 22% (50 percentage points) Latino/a caregivers: 71% to 17% (54 percentage points) |

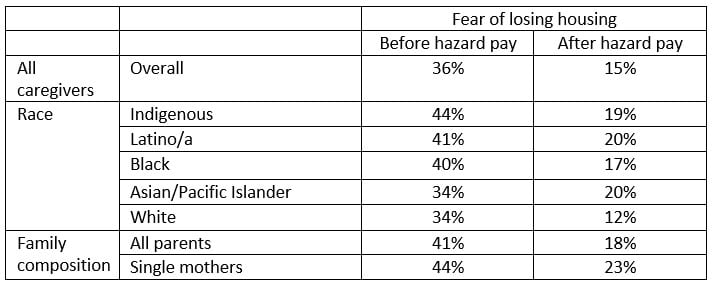

| Housing insecurity. — “Always” or “often” afraid of losing housing | 36% | 15% | 21 | Indigenous caregivers: 44% to 19% (25 percentage points) Black caregivers: 40% to 17% (23 percentage points) Latino/a caregivers: 41% to 20% (21 percentage points) Single mothers: 44% to 23% (21 percentage points) |

| Food insecurity. — “Always” or “often” worried about not having enough food | 37% | 15% | 22 | Spanish speaking caregivers: 51% to 21% (30 percentage points) Indigenous caregivers: 51% to 19% (32 percentage points) Latino/a: 47% to 22% (25 percentage points) Black caregivers: 42% to 18% (24 percentage points) |

| Mental health. — “Always” or “often” worried, anxious, or depressed about finances | 54% | 24% | 30 | Indigenous caregivers: 64% to 31% (33 percentage points) Latino/a caregivers: 59% to 28% (31 percentage points) |

| Access to health care. — “Always” or “often” avoid going to the doctor, urgent care, or hospital due to cost | 42% | 17% | 25 | Indigenous caregivers: 59% to 17% (42 percentage points) Black caregivers: 40% to 18% (22 percentage points) Latino/a caregivers: 42% to 19% (23 percentage points) |

| Savings and emergencies. — Able to pay for a $400 emergency expense out-of-pocket | 13% | 35% | 22 | Russian speaking caregivers: 4% to 13% (9 percentage points) Caregivers with children: 10% to 31% (21 percentage points) |

| Thriving. — Some money left over at the end of the paycheck | 13% | 34% | 21 | Indigenous caregivers: 10% to 40% (30 percentage points) Single parents: 9% to 31% (22 percentage points) |

Introduction

Policymakers have an unprecedented opportunity to transform caregiving and the way the U.S. healthcare system provides long-term care for older adults and people with disabilities, including individuals with complex medical needs. Despite growing demand for home and community-based services (HCBS) – opportunities for Medicaid beneficiaries to receive services in their own home or community rather than institutions or other isolated settings – home care work remains undervalued and poorly compensated with low pay and often no benefits. Predominantly women, Black, Indigenous, and people of color, and workers from low-income households, home care workers are providing essential in-home care during the most severe pandemic in recent history. Additionally, home care workers’ disproportionate reliance on means-tested financial assistance programs and self-reporting of mental health issues indicates that many are likely to have a disability themselves. In significant part due to difficult working conditions before and during the pandemic, the home care field experiences high staff turnover and staffing shortages.

The failure to value home care work and invest sufficient public dollars in the industry compromises the availability of quality care for the elderly and people with disabilities who rely on them the most. More than 800,000 people with disabilities who qualify for Medicaid are stuck on waitlists to receive critical Medicaid home and community-based support services, and many more could benefit from broader eligibility standards for these programs. Even more people who don’t qualify for Medicaid are unable to access in-home care in the private-pay market because of worker shortages and turnover. Only 30 percent of noninstitutionalized seniors who require long-term services receive paid care.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Congress delivered an emergency influx of Medicaid dollars to allow states to ease the financial strain on state funds. The Families First Coronavirus Act and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act provided money that some states used to fund hazard pay for caregivers. For example, Washington State used federal relief funds to provide 45,000 home care workers hazard pay, a temporary increase of roughly $2.50 an hour above base wage rates. Later in the pandemic, recognizing the essential nature of caregiving work, Congress passed the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), more explicitly encouraging states to invest in home care workers as essential workers.

As Congress deliberates over investments in long-term economic growth, expanding access to quality, affordable home and community-based services (HCBS) would help hundreds of thousands of older adults and people with disabilities obtain the support they need, while also creating jobs and raising wages for home care workers. Following the guidance of President Biden’s American Jobs Plan, Congress should invest $400 billion in expanding HCBS Medicaid services and supporting the long-term care workforce.

It is within this context that SEIU 775 and the Center for American Progress conducted a statewide survey sent to 42,000 home care workers who received hazard pay in Washington State. The purpose of this case study is to show the impact of the significant, albeit temporary, increase in wages. The case study found that higher wages helped to stabilize the finances of many home care workers, reducing the number who struggle with housing and food insecurity. Caregivers also reported improved mental health, well-being, and ability to save. Black, Indigenous, and caregivers of color, caregivers who speak a language other than English, and caregivers raising children often reported the most economic hardship before hazard pay and the biggest net benefit from the increase in wages. Critically, higher wages also made many workers feel more valued and less likely to leave home care. Indeed, almost half of all home care workers who started caregiving in the last year indicated that the hazard pay boost drew them to the field.

These findings add recent and relevant information to a long-standing body of research showing that improving home care job quality is critical to addressing home care shortages. Hazard pay is a temporary improvement in caregivers’ lives and in the quality and availability of home care, but it is not enough. A $400 billion investment in HCBS through the American Jobs Plan is necessary to continue the improvements seen in caregivers’ economic security, and retention and recruitment of a home care workforce that meets the needs of older adults and people with disabilities in the country.

Caregiving Policy Overview

Nationwide, more than 2 million workers provide in-home care to over 3.5 million older adults and people with disabilities who remain in their homes and need help with activities of daily living.

Although Medicare, private insurers, and individuals can cover some home care services, home care, a primary component of HCBS, is predominantly provided through Medicaid. Medicaid covers one in three persons with disabilities and provides coverage to 7.9 million low-income seniors, including five in eight nursing home residents. Indeed, state Medicaid programs are required to offer Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS) in nursing homes, while providing HCBS is optional.

The current unmet need for community-based care preceded the pandemic. According to a recent study, 9 out of 10 older adults expressed a desire to live at home as they age. Further, an estimated 74 million people living in the U.S. will be 65 or older by the year 2030, suggesting that the need for affordable home-based and community-based care is urgent. Despite a rapidly aging population driving up demand for in-home care, states regularly cite turnover and labor shortages as barriers to expanding home and community-based services.

Home care work, including the work of home health and personal care aides, remains one of the fastest growing occupations since the Great Recession, with hiring expected to jump 34 percent from 2019 to 2029. But for decades, home care has been defined as a profession with low wages, long hours, and scant benefits. It is also a job primarily held by women and Black, Indigenous, and people of color. Nearly 9 in 10 home care workers are women. More than one-quarter (28 percent) of caregivers are Black, 22% are Latino/a, and 8% are Asian or Pacific Islander.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median pay for home health and personal care aides last year was just $13.02 per hour, or $27,080 per year. Providing care is challenging, physically demanding work and often lacks health insurance, retirement, paid leave, predictable work arrangements, or other protective workplace benefits. Even before the pandemic and its economic fallout, Black, Indigenous, and communities of color, who do an outsized share of home care work, already experienced higher rates of poverty and economic hardship. During the pandemic, they have faced more severe health and economic consequences. With such work so undervalued in the labor market, it is no wonder the industry experiences high turnover and low retention.

Unlike most states that offer HCBS, Washington state offers Medicaid HCBS benefits to all enrollees who qualify. Through administrative and budget actions over the last three decades, Washington has shifted away from institutional care, in favor of HCBS. In the 1991-1993 biennium, home care made up only 16% of the Washington Aging and Long-Term Services Administration budget and served 19,000 clients. By the 2015-2017 biennium, home care had increased to 53% of the budget and served 42,000 clients.[1]

In the early 2000s, home care workers in Washington State began organizing and formed the union SEIU 775. Through bargaining with the State and private home care agencies, caregivers won better wages, benefits and working conditions. While still not enough to sustain caregivers and their families, the improvements caregivers achieved in Washington are a big step forward and a model for other states.

Medicaid-funded home care workers in Washington are employed both by private home care agencies with Medicaid contracts and through the state’s consumer directed program in which they are paid directly by the state but where clients retain much of the responsibility to supervise, hire, and fire them. The partnership is successful, in large part, because it has raised care standards without limiting consumer control and therefore won the support of disability rights and worker advocates. Today, Washington ranks second in quality of long-term health care services and supports, according to a 2020 report from the AARP Public Policy Institute.

Case Study in Washington State

As is true across the country, home care workers fulfill a critical need in Washington State. Higher wages for home care workers, in the form of hazard pay, helped to stabilize the workforce by paying caregivers to continue to do their job through the shutdowns and by boosting income just enough to mitigate caregivers’ economic crises and hardships.

Since May 2020, the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) has provided enhanced Medicaid provider rates using federal funds. In home care, the vast majority of these funds have been used for hazard pay for home care workers. These funds have provided significant economic relief to home care workers and private home care agencies and helped sustain the caregiver workforce through the pandemic.

Currently, the rates fund about $2.50 per hour in hazard pay for home care workers. Specifically, hazard pay, on average, increased caregivers’ hourly wages from $17.65 to $20.44.[2] While hardly a windfall for higher earners, this afforded an economic safety net for a caregiving workforce making poverty-level wages.

Hazard pay demonstrated how higher wages can improve job quality for home care workers. Unfortunately, the short-term nature of economic relief for the home care workforce is proving unmatched to the outsized needs for future long-term services and supports. Hazard pay is a one-time infusion of economic relief that should only be the down payment. Policymakers must do more than restore jobs to pre-pandemic levels.

Methodology/The survey

The provision of a significant, though temporary, wage increase in the form of hazard pay over the last 14 months provides a unique opportunity to evaluate the impact of those higher wages on caregivers’ health and economic well-being, as well as the ability to recruit and retain caregivers. SEIU 775 conducted an online survey with 42,000 caregivers across the State. The survey asked caregivers a series of questions about their lives before hazard pay, then repeated the same questions about their lives after hazard pay. Caregivers were also asked how they spent the additional money and how it impacted their relationship with their job.

The survey, emailed and texted to 42,000 caregivers in May 2021, was conducted online in English, Spanish, Russian, and Korean, and was completed by 5,307 caregivers, a 13% response rate.[3] All Medicaid-funded home care workers represented by SEIU 775 received the survey, with the exception of a relatively small number who previously said they did not want to be contacted. This includes workers in the State-run consumer directed program and workers employed by traditional private home care agencies contracted by Medicaid. SEIU 775 represents well over 90% of the Medicaid-funded home care workers in Washington State. All Medicaid-contracted home care agencies receive the same amount of funding for labor costs, and all received the same enhanced rate that was negotiated into hazard pay at the Union-represented agencies. There is no publicly available information on whether the remaining home care workers employed at non-union home care agencies received a pay raise through the enhanced rate, and no available list of non-union Medicaid-funded home care workers.

The survey results were supplemented by in-depth interviews with 10 caregivers across the State, conducted in English, Spanish, Mandarin, and Cantonese. Interviewees were chosen to represent the demographic and geographic diversity of caregivers across Washington State.

The demographics of caregivers who responded to the survey are consistent with what we know of caregivers across the country. Most (81%) of respondents identified as women. Respondents were disproportionately Black, Indigenous, and people of color: only 53% of survey respondents were White, compared to 79% of all Washingtonians. Asian/Pacific Islander and Latino/a respondents made up the biggest non-White racial groups (14% and 11%, respectively), although Black/African American/African caregivers (7%) were represented at almost twice their rate in the general population.[4] In addition, 2 percent were Indigenous, and 14 percent said their race/ethnicity was not listed (10 percent) or did not answer (4 percent). One-quarter (25%) of respondents identified a language other than English as their preferred language.

Despite a wide range in household size, including 18% of respondents in households with five or more people, 79% of respondents had a total annual household income below $60,000. By comparison, real median income in Washington for all households was $78,687 in 2019. More than one in three caregivers (36%) had total household incomes below $30,000, and 13% of caregivers’ household incomes were below $20,000. Many caregivers depend on these salaries to support families. Half (49%) of all caregivers said they have children.

Overall economic well-being

When asked how well they were managing financially before hazard pay, 66% of all caregivers said they were “just getting by” or “finding it difficult to get by.” This fell precipitously since hazard pay, with only 16% describing their financial situation this way. Now 84% say they are “doing okay” or “living comfortably.”

This transformation in overall economic well-being was particularly pronounced for Indigenous and Latino/a caregivers: 72% of Indigenous caregivers and 71% of Latino/a caregivers were “just getting by” or “finding it difficult to get by,” compared to 22% and 17%, respectively, after hazard pay.

Housing insecurity

Many caregivers struggle to keep up with the rising costs of housing. Before hazard pay, 44% of respondents said they missed water, gas, or electric bills, and 27% missed rent payments. In in-depth interviews, caregivers described feeling helpless to prevent these missed payments, even as they feared the impact on their families. Brenda Morgan recalled the fear of seeing eviction notices on her door and calling her mom for help to keep her family housed. Serreh Jarju recounted her conversation with her electricity company, sharing, “They’re always threatening me. I say, ‘You can come and cut it, I don’t have money to pay. But you look my kids in the eyes when you cut it.’”

Hazard pay significantly improved caregivers’ ability to keep up with rent and utilities and reduced their fear of losing housing. Before hazard pay, one in three (36%) of all caregivers said they “always” or “often” feared losing housing. Indigenous caregivers and single mothers experienced the highest rates of housing insecurity (see Figure 1). Fear of losing housing fell for caregivers in all demographics after hazard pay, dropping to only 15% overall.

Hazard pay also allowed caregivers relief from the monthly struggle to keep up with electricity bill payments. Tyrone Leach described his finances before hazard pay as a “constant juggle.” He would pay rent first and then put what he could on the electricity bill, often less than the total. Since hazard pay, he says, “It’s allowed me to actually have enough money to pay all the bills in the month.” For Sunshine Lopez, the Salvation Army used to be her lifeline to keeping the electricity on, but now, she explains, “I haven’t needed to go to the Salvation Army since hazard pay.”

Food insecurity

Several caregivers explained how they frequently ended up with little money left for food. As Lucy Bojorquez-Bellisomi put it, “Bills don’t wait.” Caregivers pay priorities like rent and car payments first, to keep from losing their housing and transportation, then cope with the consequences of low wages and expensive bills by seeking food assistance or skipping meals.

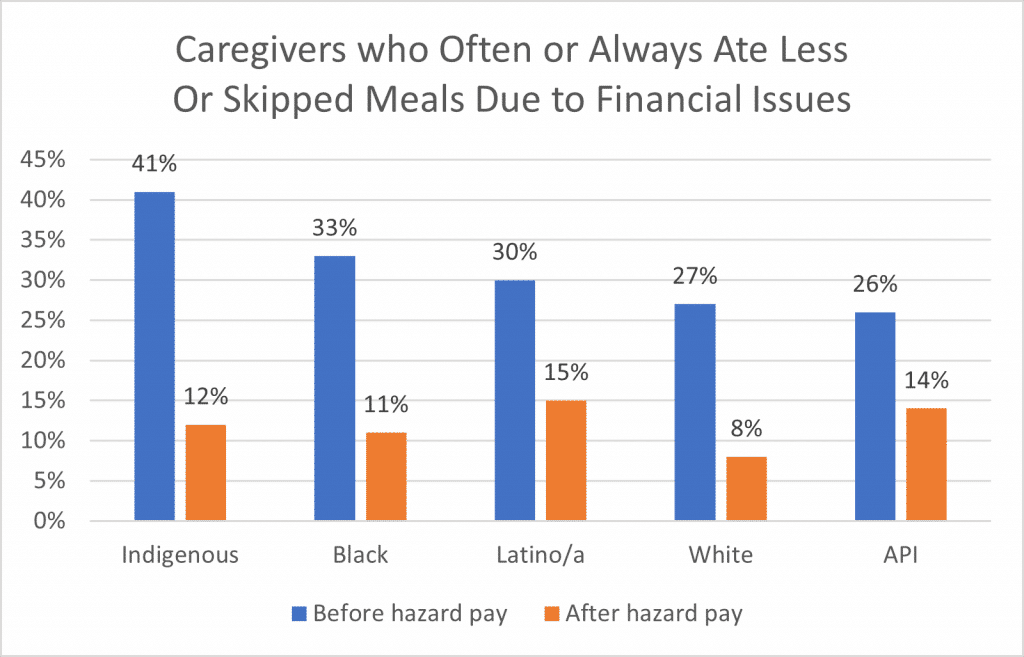

Before hazard pay, 37% of caregivers “often” or “always” worried whether they would have enough food to feed themselves and their families. Nearly one-half (46%) of caregivers applied for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), although only 25% were deemed eligible; half (51%) sought free groceries elsewhere, from food banks or religious institutions. Even with these supports, 28% of caregivers “often” or “always” ate less or skipped meals due to financial issues. Food insecurity was particularly common among Indigenous caregivers and Spanish speakers: 51% of Indigenous caregivers and 54% of people who took the survey in Spanish said they often or always worried about having enough food. After hazard pay, the proportion of all caregivers experiencing food insecurity fell to 15%, and only 10% of all caregivers ate less or skipped meals due to financial issues.

“I work 3 jobs, at least 80 hours every week, to support my mom and three kids. I have just a few times with my kids. Sometimes before hazard pay, we didn’t have food. We go to the food bank, but you’re only allowed to go so often, and with 5 people in the house it doesn’t last for more than a few days. But my kids are understanding. We just pray. They say, ‘When we grow up, we’ll work out all these things. It will be a story one day.’ Hazard pay hasn’t given us 100% of what we need, but right now we’re surviving. Because of hazard pay, we have enough food. I can go to the grocery store instead of the food bank. I pay our bills. I bought a used car so I can drive to work. I can buy a few clothes for my kids. I don’t have any money to save, but I can at least survive with this.”

— Serreh Jarju (Everett, WA)

Even for caregivers who always had food on the table, hazard pay has allowed them to access healthier food. One in three (42%) of respondents said they now purchase better quality food for their families — quality food they could not previously afford. For Jianjun He, this is important for her role as a caregiver. “I now buy healthy food with hazard pay to improve my immune system. I need a healthy body to do my job well,” she says. Lucia Apodaca echoed the same sentiment, noting, “I was able to buy some vitamins I wasn’t buying before. I’m starting to get older, [and] I have to be healthy and strong to take care of my clients, lift them, and help them move around.”

Mental health

For many caregivers, low wages before hazard pay were a source of chronic stress. More than half (54%) of caregivers – and up to 64% of Indigenous caregivers and 59% of Latino/a caregivers – said they “often” or “always” felt worried, anxious, or depressed about their finances before hazard pay. Lauren Evans described staying up late at night with worry, unable to stop thinking about how to make ends meet. Only since hazard pay has she been able to afford the sleep medication her doctor prescribed. Serreh Jarju described periods of time where she even thought about going back to her home country despite the hardships there, remarking, “I was sick. I was depressed. That’s why I don’t blame people who commit suicide.”

The mental health consequences of low wages also spill over to caregivers’ families and children. One caregiver said her 13-year-old daughter takes over child care responsibilities while her mom is at work. As a result, the young teenager tells her mom she “doesn’t want to live anymore” and “she doesn’t know if she can handle it anymore.” If wages decrease again, the caregiver will have to take on more work hours, and her daughter will have to do even more child care, threatening her mental health.

Since hazard pay, only 24% of caregivers, compared to 54% before hazard pay, continue to experience worry, anxiety, or depression about finances. Tyrone Leach explains, “Hazard pay relieves worry. You know you’re going to have enough to pay everything.” More than two-thirds (71%) of caregivers said hazard pay has meant they are less stressed or worried about paying bills on time. Serreh Jarju has also seen how the increased wages and less economic stress have brought relief to her mom and her children, noting, “They are all happier now.”

Access to healthcare

Although most caregivers in Washington working more than 80 hours per month have health insurance, meaningful access to health insurance is also influenced by their ability to pay copays and premiums. For many caregivers whose paychecks already do not cover the basics, the costs of healthcare visits and emergencies are still unaffordable. Before hazard pay, 42% of caregivers “often” or “always” avoided going to the doctor, urgent care, or hospital because they could not afford it. Since hazard pay, that has dipped to just 17% of caregivers. In the past year, 31% of caregivers have gone to a medical professional to address medical, dental, or mental health issues that they had ignored in the past because they could not afford to do anything about it.

Staying healthy in a job that requires providing intimate care to multiple clients also requires preventive measures and protective equipment. Even before COVID-19, caregivers were at higher risk of illness, as Sunshine Lopez explains, “We’re always on the front lines. If a client gets sick, we’re at risk every time. I have a daughter that’s immunocompromised. It’s something I have to think about every day, not just during COVID.” Like many caregivers, Lucia Apodaca plans to continue buying and using gloves and masks after the pandemic, even though they are expensive, because she has seen its health benefits. She cited, “Before the pandemic, when one of my clients got the flu, I would bring it back home to my family. Since I’ve started using masks, that hasn’t happened.”

“The extra money doesn’t make up for the sacrifice we make every day, the risk with our clients, the possible exposure. I’m a single mother [to] a child with autism. He needs me to stay alive. It’s a constant fear every day. My mom had COVID and she was hospitalized. I got COVID, too, and I had to stop working and quarantine. Hazard pay allowed me to reduce my hours a little [when] one of my clients was too risky and I didn’t feel safe from COVID with him. My income is still very low and finances are a stress. But at least I’ve survived. I don’t want to take that risk again.”

— Lucy Bojorquez-Bellisomi (Olympia, WA)

Savings and emergencies

Given the challenges caregivers face keeping up with basics like housing, food, and healthcare, it is no surprise that most caregivers do not have savings. Before hazard pay, only 13% of caregivers said they would have been able to cover a $400 emergency expense with the money in their checking or savings account. Although some caregivers said they had access to credit cards or loans, other caregivers described emergency measures: 22% said they would borrow from a family member or friend, 8% would use a payday loan or overdraft, and 9% would sell something. Almost one in three (31%) caregivers said they would be completely unable to afford a $400 emergency expense by any means. Lucy Bojorquez-Bellisomi expressed the fear that emergency expenses cause, noting, “That scares me. I would have no way to pay.” Jianjun He said she would “have to find an additional job.”

Since hazard pay, 35% of caregivers, up from 13% before hazard pay, now report having enough savings to cover a $400 emergency expense out-of-pocket. This is consistent with 31% of caregivers who said hazard pay has allowed them to put some money into savings. Sunshine Lopez explains, “Before hazard pay, I was living paycheck-to-paycheck with no savings account. I currently have a savings account and I paid off $5,000 in debt.”

Hazard pay has also helped caregivers reduce debt: 29% of caregivers said hazard pay allowed them to pay back family or friends who loaned them money, 43% were able to make payments on their credit card, loan, or line of credit, and 47% said it allowed them to avoid going into additional debt during the pandemic.

Prior research supports what caregivers expressed. The ability to save money and pay off debt has a significant impact on mental health.[6] Brenda Morgan celebrated when hazard pay allowed her to catch up on her bills and pay off two of her credit cards. Tyrone Leach said he isn’t hassled by debt collectors as often, since hazard pay has allowed him to catch up on payments. Sunshine Lopez explained, “For me, savings means that if my son gets hurt in the military and I have to [take] a flight to where he’s at, I don’t have to think about how I am going to get to him.”

Thriving

Well-being and livable wages are not just about survival. Before hazard pay, 52% of caregivers said finances controlled their life, compared to 31% after hazard pay. Jianjun He says, “My income was just enough to spend on daily living expenses, and I never had enough money left to enjoy life.” Due to hazard pay, the proportion of caregivers who reported being able to enjoy life because they have money to spend on personal or family activities increased from 16% to 45%.

One in three (34%) caregivers have money left over at the end of the month now, compared to just 13% before hazard pay. This allowed caregivers some ability to spend money beyond bills and the bare necessities. One-third (32%) of caregivers said they purchased things for their children that they would not have been able to afford before, like new clothes, shoes, toys, or books. One-quarter (24%) said they were able to give family or friends more holiday, birthday, or wedding presents, and 9% said they were able to go on vacation.

Sunshine Lopez described hazard pay as “the ability to get things you don’t necessarily need but you want,” though her examples were financial choices that many middle-class families would take for granted, such as a used laptop for her son to complete his studies and the drive to Idaho for her aunt’s funeral. Brenda Morgan has been able to take her family out to get ice cream on Sundays and bought a used washer and dryer, which she described as “the nicest things I’ve had in a very long time.”

Attracting and retaining caregivers

Paying home care workers higher wages also has positive impact on turnover and retention in the field. When caregivers were asked how much hazard pay influenced their decision to continue caregiving in spite of the pandemic, 55% of caregivers said it either influenced their decision “a lot” or they would have quit if there had not been hazard pay. Retaining caregivers is not only important to meet the growing demand for in-home care; it also improves care quality, continuity, and outcomes.

Among caregivers who have been working less than one year, 10% said they would not have begun caregiving if there had not been hazard pay, and another 31% said hazard pay mattered “a lot” in their decision to begin caregiving. Serreh Jarju explained that when her friends saw how much happier she is now, she told them about hazard pay and four of her friends applied to the home care agency where she works.

Higher wages also change how people feel about their jobs. More than half (57%) said they appreciate their job more since hazard pay. Jianjun He explained, “Hazard pay makes me feel like my hard work is rewarded. My work is recognized.”

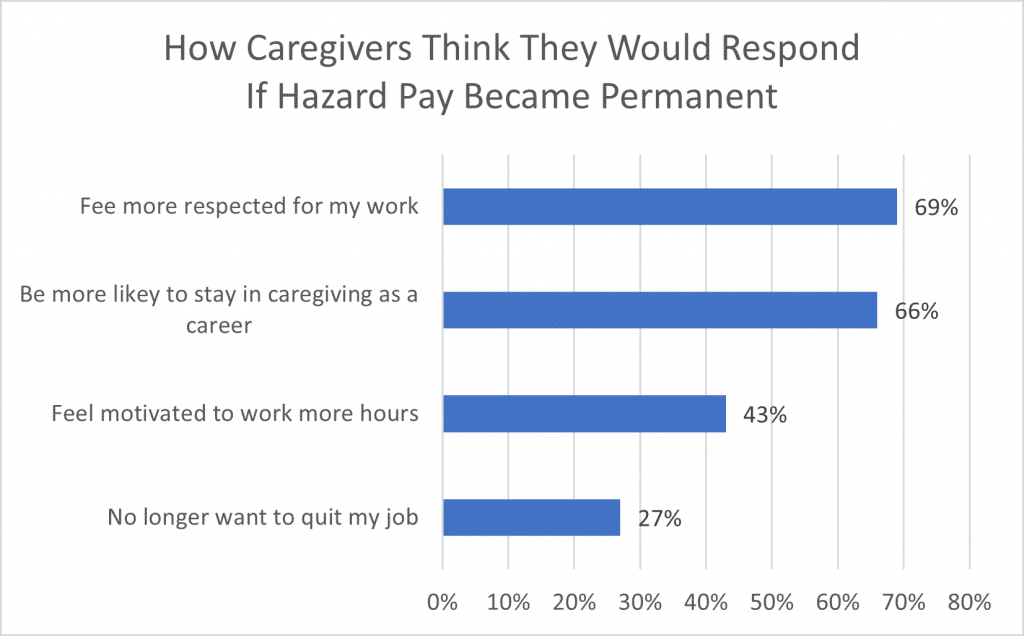

When imagining higher wages becoming permanent, 27% of caregivers said they would no longer want to quit their job, 43% would be motivated to work more hours, 66% would be more likely to stay in caregiving as a career, and 69% would feel more respected for their work. Lauren Evans, in her own housing for the first time in years, says, “I have thought about quitting my job if hazard pay doesn’t continue because I don’t want to lose my home. I love my job, but I also need to provide for my family. It’s like being stuck between a rock and a hard place.” She spoke to the growing demand for care in the country, explaining, “We need more caregivers, but there aren’t enough because the wages are so low and the cost of living is soaring. People can’t afford to do this work.”

Policy Call to Action

Home care workers do essential work. They care for our loved ones, performing intimate labor to ensure the health, well-being, and comfort of older adults and people with disabilities. Caregivers are vital to society. Yet their work is so poorly valued that they experience financial hardship and cannot make ends meet or provide for their families. As Lauren Evans explains, “We are people who give our lives to someone so that they can live theirs. We just want to live, too. Our children want to live.”

Caregivers’ descriptions of their lives before hazard pay include economic hardships and crises with significant consequences for their health and well-being. Caregivers reported crises like homelessness and chronic fear of losing housing, food insecurity, eating less and skipping meals, constant anxiety and depression, and avoiding doctor and hospital visits. These experiences are all associated with negative health outcomes, such as illness and chronic health conditions. The low wages that caregivers receive are an occupational health hazard.

Over the last year, higher wages in Washington State have dramatically reduced caregivers’ experiences of crisis and hardship. Black, Indigenous, and Latino/a caregivers saw the biggest benefit from the increase in wages. Higher wages are a source of economic security and racial equity, improving the health and well-being of all caregivers, especially Black, Indigenous, and caregivers of color.

When a few extra dollars in wages make such a difference in caregivers’ economic security and well-being, it is no surprise that those higher wages are also a driving factor in caregivers’ ability and desire to stay in the job. More than half of all caregivers reported that increased wages strongly influenced their decision to continue caregiving in spite of the pandemic, and nearly half of people new to the field said the increased wage was a significant factor in their decision to start. As the demand for in-home care grows, higher wages will help to ensure that there are enough caregivers, and that there are caregivers with enough long-term experience in the field to provide quality care.

As Congress deliberates over investments in long-term economic growth, expanding access to quality, affordable home care and strengthening job quality standards for this workforce will help hundreds of thousands of older adults and people with disabilities attain the support they need, while also creating jobs, raising wages, and reducing economic insecurity and racial inequity. Following the guidance in President Biden’s American Jobs Plan, Congress should invest $400 billion in expanding Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) under Medicaid, to deliver expanded services and higher wages and benefits for home care workers. Such an investment would attract and retain workers, afford older adults and people with disabilities the opportunity to receive care in their homes, and ensure that caregivers and their families have the resources they need to live with dignity.

[1] Moss, Bill. “Aging and Long-Term Support Administration: 101 Presentation.” Washington State Department of Social and Health Services. 17 January 2017.

[2] This is based on a calculation of the actual average wage and hazard pay paid to caregivers. The average wage varies based on agency and cumulative career hours, while hazard pay varies slightly based on agency.

[3] Response rates by language: 12% in English, 15% in Spanish, 37% in Russian, and 35% in Korean.

[4] The survey results suggest that the grouping of Asian and Pacific Islanders into one racial category may have obscured some of the economic conditions of people in these communities.

[5] The lack of disaggregated data in this study on different nationalities among Asian and Pacific Islanders may obscure food insecurity that people in these communities experience.

[6] Michael Madowitz and Christian Weller. (2021). Income or Wealth: What did the 2020 Stimulus Mean for People’s Happiness and Why It Matters? forthcoming. Challenge.